Volume 27, Issue 1, Spring 2003, Spring 2003

HACCP Implementation in School Foodservice: Perspectives of Foodservice Directors

By Jeannie Sneed, PhD, RD, SFNS; and Daniel Henroid, Jr., MS, RD

Abstract

Food safety is an issue that is receiving much emphasis in school foodservice, and there is

evidence that the incidence of foodborne illness in schools is increasing. This trend necessitates the implementation of a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points (HACCP) program in school foodservice operations, yet to date, only a small number of schools have done so. The purpose of this study was to determine best practices and HACCP implementation strategies used in successful school foodservice to serve as the basis for developing a model HACCP program for school foodservice.

All 50 state directors of child nutrition programs were contacted by e-mail to provide recommendations of school foodservice directors who had implemented–or were in the process of implementing–a HACCP program in their school districts. The 17 district school foodservice directors who were nominated by state directors were invited to participate in a modified focus group discussion. Ten directors representing nine states across the nation were able to participate. Eleven questions were developed related to HACCP implementation, resources, development, and implementation. These questions were discussed over the course of approximately 10 hours, in a two-day session.

Directors reported both internal and external factors that prompt the implementation of HACCP. Individually and as a group, they recognized that HACCP is a large and important undertaking that requires commitment at all levels within the school district, and recommended that school districts have a food safety policy in place to support their HACCP efforts.

Implementation of HACCP is a long process that is most effective when it is done in slow, progressive steps. Employee involvement, training, and empowerment are important factors if HACCP is going to be an integral part of a school foodservice operation.

Full Article

Please note that this study was published before the implementation of Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, which went into effect during the 2012-13 school year, and its provision for Smart Snacks Nutrition Standards for Competitive Food in Schools, implemented during the 2014-15 school year. As such, certain research may not be relevant today.

The importance of food safety and its role in food quality is well established (Gilmore, Brown, & Dana, 1998), yet it appears that food safety remains an issue of concern in schools. A recent U.S. Government Accounting Office (GAO) report (GAO, 2002) indicates that since the early 1990s, the number of foodborne illness outbreaks is increasing in schools by about 10% per year. It should be noted that this number may be higher than would be expected because of new data collection procedures that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began implementing in 1998. Unfortunately, there is no method to track the percentage of school- related outbreaks attributed directly to foods prepared in school meal programs.

Nevertheless, this trend in the number of school foodborne illness outbreaks demonstrates the necessity for school foodservice operators to implement Hazard Analysis of Critical Control Points (HACCP) programs. While the need seems evident, only a minority of district school foodservice operations have implemented a HACCP program. Hwang, Almanza, and Nelson (2001) found that 13% of school corporations in Indiana had implemented HACCP, and Giampaoli et al. (2002) found in a national study that nearly 30% of directors reported to have implemented HACCP.

Research is available on the implementation of HACCP prerequisite programs in schools (Youn & Sneed, 2002; Youn & Sneed, 2003), factors that influence HACCP implementation (Hwang et al., 2001), attitudes and challenges to implementing HACCP (Giampaoli, Sneed et al., 2002), and food-handling practices (Giampaoli, Cluskey, & Sneed, 2002). There is no research related to the process and success of implementing HACCP in school foodservice; therefore, the purpose of this research was to determine best practices and implementation strategies for successful school foodservice HACCP programs to serve as the basis for developing a model HACCP program.

Methodology

Sample

In September 2001, all 50 state directors of child nutrition programs were contacted by e-mail to provide recommendations of school foodservice directors who had implemented–or were in the process of implementing–a HACCP program in their school districts. Seventeen individuals were nominated from 12 states. Two states responded that they did not have anyone implementing HACCP. Other state directors did not respond.

Each nominee was mailed a letter of invitation to participate in a modified focus group discussion. A convenience sample of 10 district school foodservice directors participated in the focus group. These directors represented nine states (Arizona, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin). A representative from the National Food Service Management Institute (NFSMI), who is involved in developing HACCP programs and providing HACCP training, also participated in the discussion group.

Research Design

The modified focus group session was held in November 2001 to explore best practices and strategies for HACCP implementation. Researchers developed 11 questions related to HACCP implementation, resources, development, and implementation. In the discussions, these questions were modified slightly and other general information important for HACCP program development and implementation was covered. More questions are included than those developed by the focus group. More accurately, it is the responses of the focus group that follow. Group participants spent 10 hours over the course of the two-day session discussing specific questions. Prior to discussion, the group was divided in half, and both groups recorded their responses on large sheets of paper that later were shared with the entire group. The presentation of these small group responses often elicited further discussion. Researchers used this technique as a way to ensure that all group members could provide input to all questions. The purpose of the discussion was to elicit a breadth of information and ideas, and participants were not asked to provide rankings or ratings for the various responses.

Results And Discussion

Questions and responses of the focus group are as follows:

Question 1: What was the impetus for beginning a HACCP program in your school district?

The impetus for beginning HACCP varied greatly among the 10 school foodservice directors, and was both externally and internally driven. The major external factor was very strict health department requirements in some states/municipalities. For example, one school district has three inspections per school per year, as well as an annual HACCP inspection.

Some school foodservice directors were not required to implement HACCP, but did so for a variety of reasons, such as recognizing how young children served in the program are particularly vulnerable to foodborne illness and a fear of the consequences if the district did not have a HACCP program in place. Comments were made about the fear of making a child sick and being featured on the front page of the local newspaper. Some participants viewed HACCP as an insurance policy; without it, school districts have greater liability.

Another factor that influenced HACCP implementation related to the foodservice system or management requirements of the operation. Two directors have a centralized foodservice system for which HACCP is imperative. Another participant worked for a foodservice management company that requires HACCP and has its own HACCP program.

Several directors indicated that they became interested in HACCP following the Jack-in-the-Box foodborne illness outbreak in 1993. Thus, that outbreak appears to have served as a pivotal point in foodservice professionals’ awareness of food safety and the serious consequences of a foodborne illness outbreak.

Question 2: What resources did you use to develop your HACCP program?

Resources used by school foodservice directors for developing HACCP programs generally fit into three categories, as follows:

- Food and foodservice operations were obvious resources. School foodservice directors looked to other operations for models for implementing HACCP. Directors visited hospitals, nursing homes, restaurants, and a grocery store to determine how HACCP was implemented in those operations. One participant noted that the HACCP materials used in the seafood department of a grocery store were particularly useful, and another director visited a food manufacturing plant to observe how it implemented HACCP, and then worked with the quality assurance department manager to develop HACCP procedures for the district’s school foodservice operation.

- Health departments and universities were important sources of information about HACCP. Some directors worked closely with the local health department and sanitarian, while others indicated that the health department was of little assistance. Interestingly, one district school foodservice operation actually served as a role model for the health department, while other directors worked with university faculty and the cooperative extension service staff on development of HACCP. One school foodservice director worked with a consultant from a local community college.

- Commercial companies were used in a variety of ways. Two directors worked for foodservice management companies; one used a corporate-developed HACCP program and the other used materials developed in her Some directors mentioned that they used materials from the National Restaurant Association’s Educational Foundation or the state’s restaurant association. One director attended Tyson University. Equipment companies (e.g. Cleveland Range) and chemical companies (e.g. Ecolab and SFSPac) also were useful resources for directors. One suggestion was to use an outside consultant to keep the process on track. If time is an issue, consultants might be able to get a HACCP program launched more expediently because of their expertise. In this example, the consultant also was able to help in revising documents and recipes, as a way to avoid increasing employee workload.

Question 3: What recommendations do you have for developing HACCP resources that are relevant and user-friendly?

The school foodservice directors had several recommendations for developing HACCP resources. Recommendations related to what resources need to be developed, as well as to the format/delivery of those resources. Directors emphasized practicality of resources, making such statements as “focus on practical applications that are easy to monitor” and “resources should be operational-focused.”

Content of resources. In addition to the standard HACCP information, directors encouraged researchers not to focus on critical control point versus control point because they believe that there is only a small difference in definition between these and the distinction is confusing to employees. The directors indicated that there was a need to develop written standard operating procedures. In addition to HACCP content, directors indicated that there was a need for educational materials related to processes such as leadership and decisionmaking. These materials would help directors focus on improving employee self-esteem.

Format/Delivery of resources. Directors recommended that researchers:

- Develop the following components: samples of forms, lesson plans, self-assessment checklists, and scenarios;

- Develop 10-minute food safety inservice training programs that include an activity;

- Use a corporate approach by conducting group meetings, encouraging sharing among directors, and providing materials on a diskette/CD in a word-processing format.

- Develop different resources for different audiences; and

- Develop materials so that they integrate into existing procedures. For example, directors recommended that HACCP components be added to existing computer software

Question 4: What content is needed for HACCP education/resource materials?

School foodservice directors were aware of the HACCP educational materials available from the National Food Service Management Institute (NFSMI). They believed that more information/emphasis is needed in other areas including procurement, handling reports of foodborne illness, and training.

Procurement. Materials should provide boilerplate language for specifications, requesting that all vendors send a letter indicating that they have a HACCP program in place or follow good manufacturing procedures (GMPs). Materials also should advise operators to check all delivery trucks for proper temperature and cleanliness.

Handling reports of foodborne illness. Directors believe that it is imperative for each school district to develop a crisis management plan, which includes how to respond to an individual who is reporting a foodborne illness and the steps to take in the process. It was noted that the first person who interacts with the reporter of the incident is pivotal, and there needs to be a focus on how that individual should deal with the situation.

Training. Directors indicated that there is a need to document training sessions with tests and sign-in sheets. Thus, these resources would be useful for school foodservice directors.

Question 5: What is the most effective method to disseminate HACCP education materials?

There are several groups of individuals who should be involved in the dissemination of HACCP education materials. Those groups include state agencies, professional organizations, and computer software companies. It was suggested that researchers work with state agencies to develop a list of resources that are already available. Once new resources are available, it is important to inform state agencies because they need to “push” HACCP and resources.

Additionally, directors indicated that it is important to coordinate with other organizations to post information about HACCP resources on their Web sites. These organizations include state agencies, NFSMI, and the American School Food Service Association (ASFSA). They also suggested working with the Association of School Business Officials International (ASBO) and ASFSA’s state affiliates to implement HACCP in schools.

It was suggested that existing computer software programs, such as NutriKids, incorporate HACCP steps. Thus, a need for HACCP information and documentation in software programs must be communicated to software companies.

Question 6: What are your recommendations for implementing HACCP?

School foodservice directors emphasized that HACCP implementation is a process that is never complete. They stated that HACCP should be practical to apply, employee-focused, andimplemented in stages. New foodservice equipment, both large and small, may be needed to support HACCP.

Practical. Directors stressed that HACCP and HACCP components need to be planned so that they are practical. They stressed that HACCP cannot be a manual that “sits on a shelf.”

Employee-focused. School foodservice directors also stressed the need to instill standards and expectations (e.g. a sense of pride) in staff, and do this in a positive manner. The directors mentioned the need to empower staff to make decisions related to HACCP and food safety.

They discussed the need to include HACCP implementation or other food safety practices as criteria for evaluating employees. Foodservice managers need to discipline employees who do not follow food safety standard operating procedures. Because of this, staff training is important. One director mentioned the need to rotate staff and cross-train them to work in different areas.

Directors also referenced the need to seek feedback from employees on the HACCP program, asking them what does and does not work in the way it has been implemented. In one example, a foodservice director printed off recipes and asked employees to record what differences in actual preparation procedures compared to the standardized recipe, a process she called “red-lining.” Such feedback facilitates changes for the future, and will become more rapid. There must be a process in place to review and incorporate such feedback.

Implement in stages. The directors participating in the focus group stressed the need to implement a HACCP program in stages with a slow and steady progression. For example, one district used a three-stage process to begin HACCP:

- Stage 1: Training, using thermometers, and recording

- Stage 2: Using all charts, initial them, and adding HACCP steps to

- Stage 3: Posting of all logs on equipment,

In another district, a few targets were selected for the first year, with the first target being the institution of temperature logs. It appears that taking employees through the process in small, achievable steps is preferred to “rolling out” a complete HACCP program that might overwhelm employees who are expected to implement the system.

Directors recommended that school districts have a district-wide food safety policy. They also mentioned the need to market HACCP to school administrators (superintendents and school business officials), as well as to such groups as the national and state ASBOs. Additionally, there is a need to consider new resources, such as portable handwashing stations. One director mentioned that “gadgets,” such as digital thermometers, often motivate employees to implement tasks related to HACCP. Student perceptions of the food (is hot food hot, cold food cold?) also should be determined.

Question 7: How much time is required to implement HACCP?

School foodservice directors indicated that the time required for HACCP implementation is very difficult to estimate and varies greatly among operations. In addition, because HACCP implementation is an ongoing process, all foodservice directors who participated in the focus group believe they still have more to do. They indicated that extensive preparation is required to implement HACCP and this can be very time consuming. Furthermore, the starting point (Are prerequisite programs in place? What components of a HACCP program are in place?) for HACCP implementation in an operation impacts the time required. They recommended that an assessment tool could be used to evaluate the school district and form the basis for developing goals. They stressed that HACCP goals must be reevaluated constantly.

Focus group participants have been working on HACCP implementation from one to six years. It took one district three years to get recipes and a food flow chart completed. One director emphasized that grouping items to develop procedures is one effective method that can be used to save time.

Question 8: How will we know that school districts have implemented HACCP?

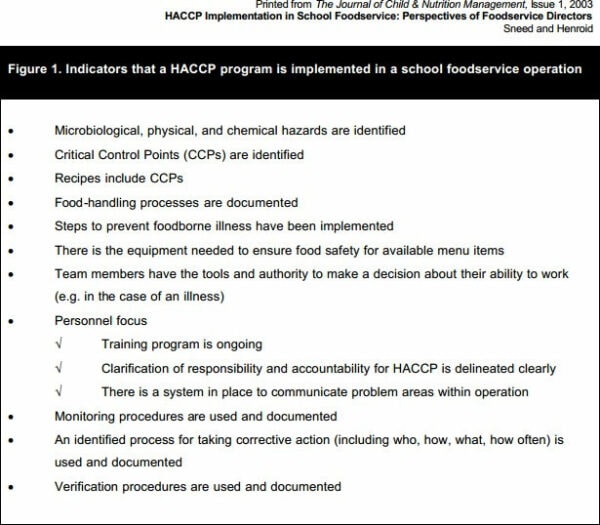

School foodservice directors indicated that schools that have implemented a HACCP program will have several components in place ( Figure 1).

Question 9: What challenges did you face in developing and implementing your HACCP program?

Challenges in developing and implementing a HACCP program were related to the following:

- State/local health departments: Directors perceived state and local health departments to have an inconsistent understanding and application of HACCP.

- Employee issues: Several employee issues may pose challenges. One such challenge is employee attitude. It is critical to get staff to “buy in” to the program. There often is the mindset that “we haven’t made anyone sick, so we must be doing everything right,” or “Why change?” Another factor is that employee self-esteem often is low. Time/responsibility of employees is yet another Employees think that HACCP is an additional responsibility and that they do not have time to implement such a program. Also, the employee union may request more time for employees to do HACCP- related tasks. The ability of employees to make good decisions may be limited, and employees often are not empowered to make good decisions. Many school foodservice operations have employees with limited reading ability, which creates a comprehension problem with much of the in-depth HACCP information. High employee turnover rates, limited dedication of staff members, and the lack of understanding about the need to document are other employee challenges.

- School culture: The school culture also may present challenges. Sometimes there are negative perceptions by teachers and staff who compare school foodservice operations with outside foodservice operations–often, there is a double standard. The culture of the community and the school may not be Other departments, such as custodians and teachers, may impact the foodservice operation. In some districts, employees may be both cooks and bus drivers.

- The foodservice system’s structure: There are instances when the school and foodservice systems are so structured that it limits an employee’s ability and willingness to make decisions. Also, there is a major time commitment to implementing HACCP. Directors need time for training employees and for developing, implementing, and monitoring HACCP implementation; and that time may be limited.

Cost issues also are a challenge, especially as they relate to current meal prices. Often, there is a need to replace equipment and purchase items such as thermometers. Also, there is need for financial support for secretarial services, printing, etc., that can be time consuming and costly.

Other issues, such as defining HACCP, keeping processes current, and knowing where to begin and end can be frustrating challenges for directors, as well as for employees. Another challenge is that procedures and forms do not always work out the first time. For example, one district reported that they changed the format of their recipes four times to ensure clarity.

Question 10: What advantages are there to having a HACCP program?

It was interesting to note that school foodservice directors participating in this discussion were very positive about HACCP and indicated many advantages to having a HACCP program implemented in their districts. HACCP programs can save money and time and can improve quality. Specific ways that money and time were saved in the districts of directors in this study were as follows:

- Decreased food waste occured because less food was discarded due to the lack of documentation of how long it was in the temperature danger There can be savings in power outage situations if temperature monitoring is done (e.g. a data logger does continuous temperature monitoring), and some equipment purchases may not be needed if temperature can be controlled with existing equipment.

- Data from the monitoring process can be used to document the need for new equipment or equipment repairs.

- Work methods can change (for example, using cart covers rather than covering individual pans).

- The process of standardizing recipes resulted in cost savings because both preparation steps and critical control points were reduced, or the time the food was at the critical control point was reduced.

Question 11: What motivates employees to follow HACCP?

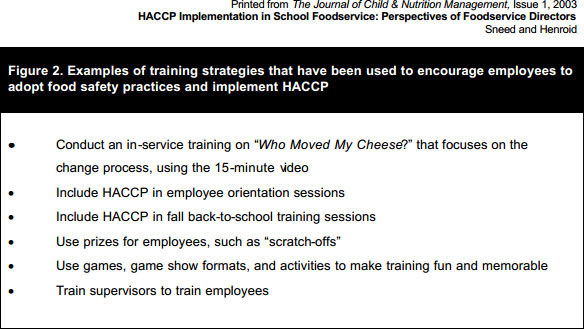

Four motivators that emerged from the discussion were professionalism, pride, scare tactics, and guilt. Training was used as the vehicle for communicating these motivators to employees and encouraging them to implement food safety practices and a HACCP program. Examples of strategies used by foodservice directors are summarized in Figure 2.

Directors indicated that they often find it a challenge to “prove” that school foodservice employees are professionals, both to the employee and to others. They believe that having a HACCP program is one indicator of professionalism.

Other strategies that have been tried included explaining the seriousness of HACCP and following up with employees on related rules. The directors suggested seeking ways to make it “cool” to do HACCP. Directors have issued pins, nametags, and ribbons as motivators, as well as providing jewel pins to managers.

Foodservice directors indicated that they avoid using the term HACCP because it can be intimidating. Instead, they focus on upgrading food safety standards. Developing supervisor skills (in HACCP, training, employee motivation, etc.) is critical for a HACCP program to be successful.

General Recommendations/Comments

Throughout the discussion sessions, important ideas were expressed that did not relate specifically to the questions. Following are some specific recommendations of or comments by the school foodservice directors:

Establishing a school food safety policy. When crafting such a policy, school foodservice directors should include such information as:

- Who has keys to the kitchen?

- Who can serve food in cafeteria? Must there be a person certified in food safety on site during the preparation and service of food?

- What foods may be served in the classroom? Can food be brought from home?

The directors identified other tips to consider when implementing HACCP.

- Avoid using the term HACCP if Use “food safety,” “food quality,” or other generic term.

- Educate yourself on food safety and HACCP Make sure you have a good understanding of what is and is not part of a HACCP program.

- Work closely with health department staff Use processes and equipment that they recommend.

- Look at the “big picture” and prioritize Make sure early steps are fully in place before moving on to later steps.

- Monitor the availability of resources (What new equipment or “gadgets” are available? What works?). Purchase infrared thermometers for receiving.

- The focus should not be on recipe flow Generally, they are a waste of time and are irrelevant to what is done on a daily basis.

- Prepare a facility food flow chart

- Everyone in the operation needs to be involved in the food safety process at the appropriate time. Some directors believe that it is not necessary to involve line employees in the initial system development.

Conclusions And Applications

Questions presented in this paper are likely to be those that would be asked by any foodservice director considering HACCP implementation or by individuals or organizations (such as NFSMI or ASFSA) who are developing educational materials to support HACCP implementation in schools. Results of this discussion show that HACCP implementation is a large and important undertaking that requires commitment at all levels within a school district.

School foodservice directors should work with school administrators to develop a school-wide food safety policy if there is not already such a policy in their school districts. It seems that such a policy would provide a strong foundation for overall food safety for students and for implementing HACCP, not only for school meals but for other foods eaten in the school (in the classroom, at fundraising and sports events, and at group meetings).

School foodservice directors who have implemented–or are in the process of implementing–a HACCP program, have used many resources in the process. Sharing these will provide useful information for directors who are just starting the process. Results from this focus group provide some realistic expectations for foodservice directors about planning and implementing HACCP that may make the process easier. Directors in the study agreed that HACCP is an ongoing process that is most effective if undertaken in slow, progressive steps. Employee involvement, training, and empowerment are keys to making HACCP an integral part of a school foodservice operation.

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Cooperative States Research, Education, and Extension Service, Project No. 2001-51110-11371. The mention of trade or company names does not mean endorsement. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of USDA. We would like to thank and acknowledge the contributions of the participants of the focus group discussion.

References

Giampaoli, J., Sneed, J., Clusky, M., & Koenig, H.F. (2002). School foodservice directors’ attitudes and perceived challenges to implementing food safety and HACCP programs. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 26 (1). Retrieved June 20, 2002,

from http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/02spring/giampaoli1/

Giampaoli, J., Clusky, M., & Sneed, J. (2002). Developing a practical audit tool for assessing employee food-handling practices. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 26 (1).

Retrieved June 20, 2002,

from http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/02spring/giampaoli2/

Gilmore, S.A., Brown, N.E., & Dana, J.T. (1998). A food quality model for school foodservices. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 22, 32-39.

Hwang, J.H., Almanza, B.A., & Nelson, D.C. (2001). Factors influencing Indiana school foodservice directors/managers’ plans to implement a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) program. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 25, 24-29.

U.S. General Accounting Office. (2002). Food safety: Continued vigilance needed to ensure safety of school meals (GAO-02-669T). Washington, DC: Author.

Youn, S., & Sneed, J. (2002a). Training and perceived barriers to implementing food safety practices in school foodservice. The Journal of Child Nutrition & Management, 26(2). Retrieved April 16, 2003, from http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/02fall/youn/

Youn, S., & Sneed, J. (2002b). Implementation of HACCP and prerequisite programs in school foodservice. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103, 55-60.

Biography

Sneed and Henroid are, respectively, professor and extension specialist, Hotel, Restaurant, and Institution Management, Iowa State University, Ames, IA.